Tensions within NATO could soon reach a breaking point as countries in Southern and Western Europe, thousands of kilometres from Moscow, resist efforts from Eastern European countries — and pressure from US President Donald Trump — to raise their military spending to a new target figure of 5% of GDP.

NATO ministers last week agreed in principle to raise security-related spending to 5% of GDP by 2032: 3.5% directly on military expenditure, and 1.5% on related matters including infrastructure and cybersecurity. US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth urged European members to “pull together” in response to the new threat environment.

On Monday, NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte warned that Russia could be ready to attack the alliance within five years, urging European members to accelerate defence spending plans. Speaking in London, Rutte called for “serious preparation” and said European forces must be able to hold their own if the US cannot immediately step in.

A summit in The Hague on 24-25 June will test their commitment. “The American message is clear: If Trump comes to The Hague, he’ll need to go back to Washington with 5% in the pocket,” Sven Biscop, director of the Egmont Institute, a Brussels-based think tank, told The Parliament.

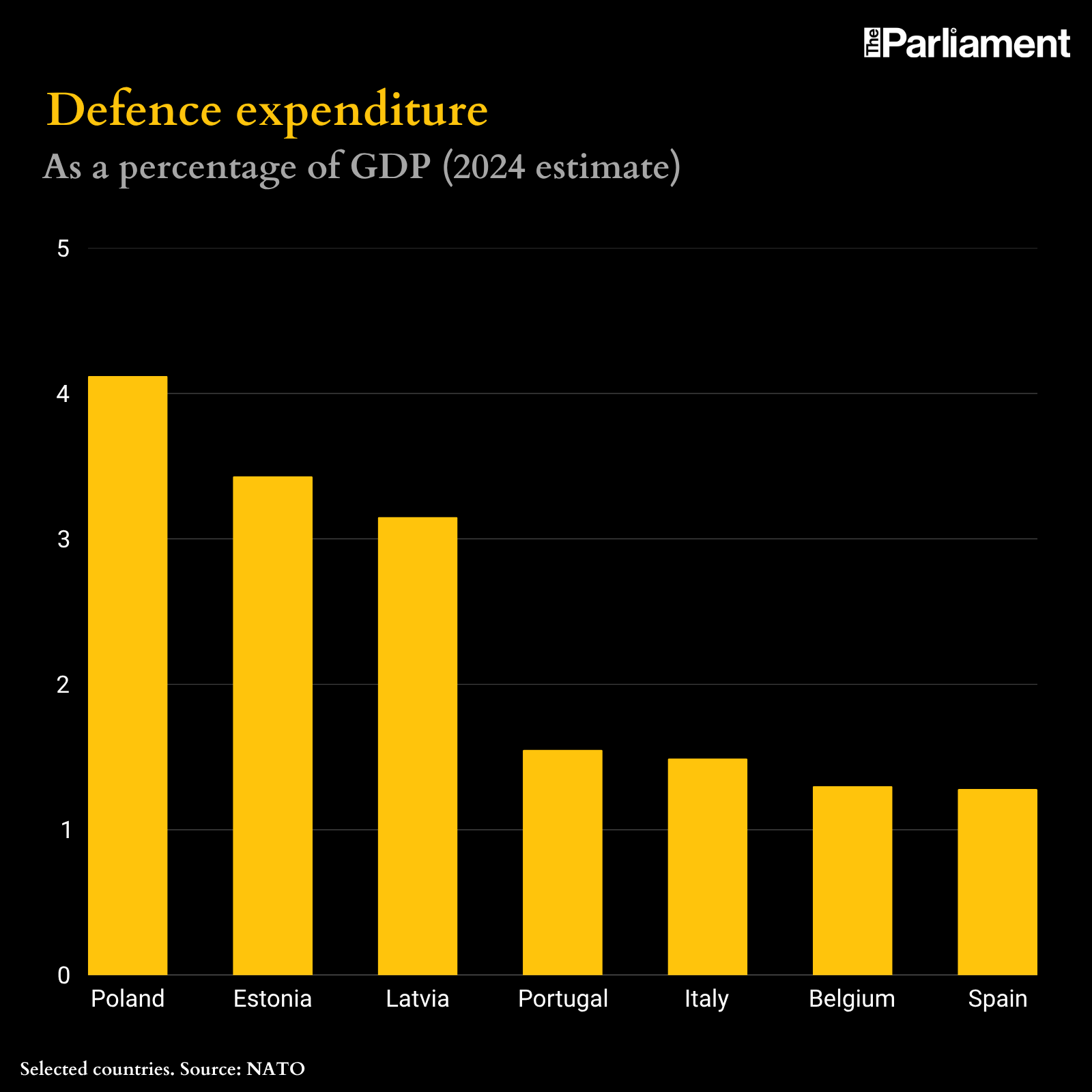

But reaching a 5% target would, for many countries, mean tripling their current spending levels. The likes of Spain and Portugal are still falling well short of the existing 2% target, and have resisted informal calls from other members of the alliance to increase defence spending to 3% of GDP.

Others such as Belgium and Italy are already running high budget deficits with no obvious way to raise the extra funds, short of politically risky welfare cuts. In some European countries, meeting the 5% target would put fragile coalition governments at risk of collapse.

“Many countries feel that the new target is simply not realistic, that they are not going to achieve this unless they do things like dismantle social security,” Hendrik Vos, professor of European studies at the University of Ghent, told The Parliament.

Trump, Russia and the push for 5%

NATO’s spending target hasn’t increased since 2014, when the 2% target was set at a summit in Wales shortly after Russia’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

While 23 of NATO’s 32 members now meet the 2% goal, pressure to go further has intensified since Trump, who has accused Europe of freeloading under the US defence umbrella, returned to office. It was the US president who first floated the 5% figure in January, shortly before being inaugurated for his second term.

But it’s not all about Trump. Russia has greatly ramped up its military recruitment and production as its war of aggression in Ukraine enters its fourth year. A ceasefire agreement might require European NATO forces to deploy to Ukraine to deter renewed aggression from Moscow, while also guarding their own borders against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s expanding military machine.

“If you look at Europe’s defence capability, there’s a genuinely honest, threat-perception-based argument to say the 5% target is necessary,” Charly Salonius-Pasternak, a leading researcher at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, told The Parliament. “European countries need to make sure they have the air forces, the infantry brigades and divisions. And that costs money.”

The European Commission has stepped in, allowing member states to increase defence spending by up to 1.5% of GDP annually for the next four years without triggering the bloc’s strict deficit rules, which usually impose penalties when budget deficits exceed 3% of GDP.

Eastern and Northern NATO members including the Baltic states, Poland, Finland, and Denmark are largely supportive of the 5% target. These countries see the Russian threat as immediate and existential, and many have already ramped up their defence budgets.

Several Eastern European countries including the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia and Bulgaria have also signed a joint declaration with Nordic countries pledging to work towards the 5% goal.

“There is a clear division between member states on the issue,” Vos said. “A number of countries, mainly in the north of Europe, were already in favour of a substantial increase in defence spending anyway.”

Poland has increased spending to a planned 4.7% of GDP this year, up from 2.23% in 2022, driven by borrowing and strong public support. Estonia has approved an extra €2.8 billion in defence spending over four years to meet NATO capability targets, and Finland unveiled a major tax reform, aimed at supporting higher defence spending.

“Poland and the Baltic states have a memory of communist rule, know what the Russians are capable of and now see what is happening in Ukraine,” Wannes Verstraete, researcher at the Free University of Brussels, told The Parliament. “Western Europe and Southern Europe do not have that historical awareness.”

NATO’s geographical divide in Europe

In countries far from Russia, there is little appetite for such drastic increases and domestic political pressures weigh heavily. Spain, in particular, has openly rejected the 5% target.

“Spain lacks an evident, manifest existential threat,” Michele Testoni, adjunct professor at IE University in Madrid, told The Parliament. “Only very recently, due to an increasing amount of pressure, Spain has timidly started to increase defence spending.”

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez recently confirmed that Spain will meet the existing 2% goal only by the end of this year — and even this plan has stretched definitions to bring a wide range of non-military spending under the “defence” umbrella.

His government has been keen to stress that, for Spain, 2% is sufficient. “We respect those who pursue the 5% target, but we believe 2% is enough to meet our capability commitments,” Defence Minister Margarita Robles said after last week’s talks in Brussels.

Public sentiment in Spain remains strongly opposed to diverting more funds from social programmes to defence budgets — a political reality Sánchez cannot ignore. “The current parliamentary coalition, which is a minority coalition, doesn’t want to increase defence spending. They rather want to increase social spending,” said Testoni.

Belgium faces similar political discord. The country is struggling to structurally fund the 2% target it committed to earlier this year, and Prime Minister Bart De Wever previously called Trump’s request “completely crazy.”

The country’s €12.8 billion defence funding plan remains unfunded beyond this year, and further increases seem politically and financially out of reach.

Foreign Minister Maxime Prévot labelled the 5% proposal “excessive” and argued that even 3.5% is “unfeasible” in the short term. But Defence Minister Theo Francken, from De Wever’s right-wing NVA party, last week signalled openness to NATO’s target — drawing immediate pushback from other coalition partners.

“The 5% target is unachievable” for Belgium, Biscop said. “But I think everyone knows 2% is the minimum, and we actually have to get to 3% or 3.5%,” noting that Belgium reached that level during the Cold War. “It is not that far-fetched of an idea.”

Italy also faces enormous budgetary pressure. Having only recently reached the 2% mark, it would need to find more than €60 billion per year to hit 5% — an almost impossible task as its national debt now exceeds €3 trillion, a record high.

Portugal is unlikely to reach even the current 2% goal until 2029; and Luxembourg has signalled doubts about how quickly it can ramp up spending, despite political support for increasing defence budgets.

Timing could undermine NATO unity

Most countries are now at least paying lip service to the 5% target. But achieving it in practice is another question; the real disagreement is likely to emerge in negotiating the timelines within which the target should be met.

Rutte has indicated that gradual increases will be acceptable, but countries like Lithuania are urging faster action. Defence Minister Dovilė Šakalienė has warned that waiting until 2032 could be too late. “The war could already be over by then,” she said last week.

Poland and other Eastern European members are also pressing for a faster trajectory, while countries like Belgium, Spain and Italy are lobbying for more time.

According to one diplomat, these reluctant countries have begun informally referring to themselves as the “group of ten,” pushing for a ten-year timeline to reach 5%.

"A sense of cohesion within the alliance requires the Northern countries to take seriously the concerns Southern states have in terms of security and what’s feasible as well. It goes both ways,” said Salonius-Pasternak.

Rutte has suggested flexible national roadmaps and interim targets to keep the alliance united, but consensus remains elusive.

“You can try to set the timeline in detail. But ultimately, a country still decides on its own defense spending. If they don't meet a deadline, there’s little to be done about it,” said Biscop.

In the meantime, the US is keeping up the pressure. Deputy Defence Secretary Matthew Whitaker warned last month: “We cannot have another Wales pledge where a lot of allies don’t meet their commitments until year 10 or year 11.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.