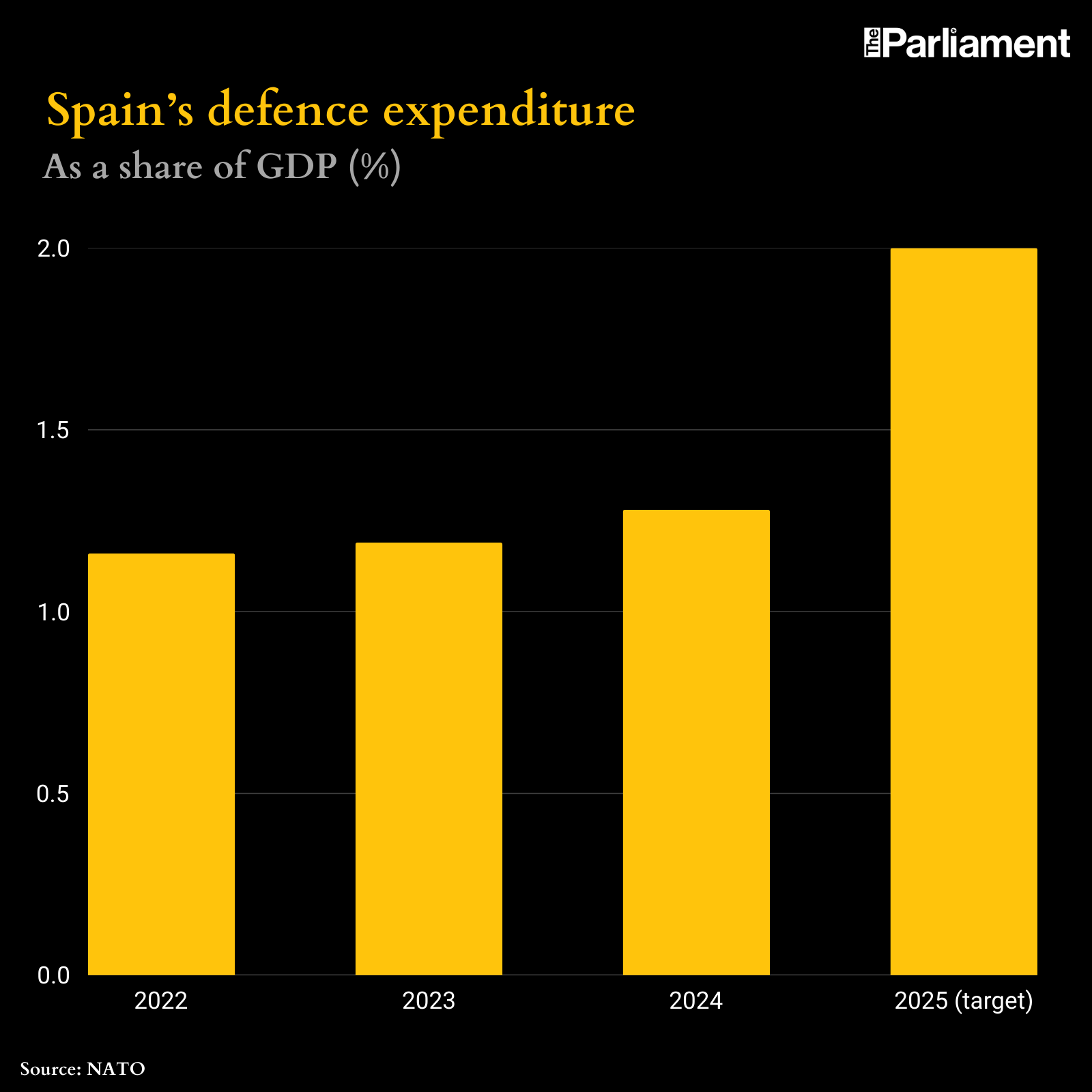

Spain’s recent uptick in defence spending ought to be good news for NATO military alliance. The long-time laggard pledged last month to meet the alliance’s defence spending target of 2% of GDP by the end of 2025, up from just 1.28% last year.

But beneath the surface, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has been stretching the definition of military spending to meet Spain’s other needs, from migration to climate resilience. Anyone hoping for a new Spanish tank division to reinforce European countries bordering Russia is likely to be disappointed — and that could lead to future arguments among NATO’s European members, or with the Trump administration in the United States.

Kaja Kallas, the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs, has been clear that defence spending should be seen as a collective endeavour to protect frontline countries against the existential threat of Russian invasion.

“[Although] Russian tanks won’t reach the Pyrenees, we have to stick together on this,” she told Spanish newspaper El Mundo in March, in an effort to persuade the Spanish public to support more defence spending.

On Monday, EU Defence Commissioner Andrius Kubilius called for Spain to reach a 3% threshold to counter Russian aggression. Kallas and Kubilius are from Estonia and Lithuania, respectively — both once part of the Soviet Union, which today feel the most at risk of further Russian aggression.

Last month, Sánchez said that 17% of this year’s military spending would go to natural disaster relief. While there’s a security-based case to be made for bolstering climate defences — Spain suffered devastating floods last year — it’s probably not what top NATO brass had in mind.

“If Spain only emphasises the civil defence part, that does not actually increase deterrence Europe- or NATO-wide,” Charly Salonius-Pasternak, leading researcher at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs, told The Parliament. “For there to be a meaning to the whole thing, it needs to actually show up in usable military force at large scale.”

Domestic challenge

Sánchez faces a balancing act at home. His Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) is supported in government by the leftist Sumar alliance, which has already branded the initiative to raise defence spending "incoherent" and "exorbitant," warning it undermines Spain's welfare priorities. Sumar’s MPs recently supported a failed motion calling for Spain to leave NATO entirely.

Economically, despite economic growth of 3.2% in 2024 and unemployment at its lowest level in 16 years, more than a quarter of the population remains at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Youth unemployment and soaring housing costs continue to generate frustration, particularly among younger voters.

“Sánchez’s main problem is coming from the left,” Oscar Martínez Tapia, adjunct professor at IE University in Madrid, told The Parliament. “He is not going to find support for defence expenditure with Sumar, who are very anti-NATO and anti-American.”

Despite Sánchez’s repeated assurances that the additional spending would not lead to increased taxes or raids on the welfare state budget, “the proper left-wing are still worried that putting more money in defence means cutting social programmes,” Martínez said.

Compliance with the 2% norm is becoming a necessity for Spain and others to be taken seriously in diplomatic circles. But because no serious budget increases have been implemented for years, the blow is particularly hard. To meet the target by 2029, the government must more than double the defence budget, which was €17.5 billion last year, to €36.6 billion.

Broader definitions

To ease concerns, Sánchez has pledged to take the money from EU Covid recovery funds and underused domestic resources, while insisting that it can be directed into the local economy and address concerns beyond strictly military ones — including migration, cybersecurity and climate change mitigation.

Sánchez, who objected to the EU’s use of the term “rearm” in the bloc’s defence package, has rebranded Spain’s €10.5 billion initiative as the “Industrial and Technological Plan for Security and Defence” — a programme he insists prioritises strategic autonomy and economic returns.

While others look with trepidation to the east, Spain looks south with greater urgency. The Sahel region of western Africa has become a major source of irregular migration to Spanish territory — and from there, potentially, to other parts of Europe.

“Sánchez is thinking a bit more big picture,” Martínez said. “The government thinks that helping Africa will lower migration to Spain and weaken the anti-immigration discourse of the parties on the right.”

Spain has also grown wary of its neighbour Morocco, emboldened by Donald Trump's 2020 recognition of Western Sahara as Moroccan territory. Tensions persist over the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, to which Morocco has repeatedly laid claim.

“All eyes in Europe are currently on the east, but the threats from the south will also only keep increasing,” Michelle Haas, researcher at the Ghent Institute for International and European Studies, told The Parliament.

Sánchez’s success in spending the defence funds on this more diverse set of concerns, and convincing the Spanish people that it’s money well spent, may depend on his ability to persuade his partners in the EU and NATO that it’s a legitimate use of funds, even as many of them would prefer to see beefing up against the Russian threat.

So far, Sánchez has struggled to put Europe’s southern border high on NATO and EU agendas. The bloc's modest agreement with Mauritania to reduce migration flows underscores the limited traction Madrid has gained.

Falling short

Countries on NATO’s eastern flank, like Poland, Estonia and Lithuania, see Spain’s defence expenditure as falling short of the alliance’s deterrence needs. Northern and eastern states have dramatically increased investments in conventional military capability, with Poland set to spend 4.7% of GDP on defence in 2025. For these countries, hard power remains the bedrock of European security.

“For long-time free-riders like Spain, the invasion of Ukraine wasn’t a true wake-up call,” Haas said, pointing out that Spain’s defence expenditure only rose slightly in the first years of the war. “But with the current transatlantic tension, diplomatic pressure on Spain has mounted.”

This year’s NATO summit, to take place between 24-26 June, is likely to bring calls from Secretary General Mark Rutte — not to mention Trump — for member countries to increase spending above 2% of GDP. Attention may also turn to how effective that spending is at countering the conventional military threat from Russia.

“Spain is a big country with geographical realities. I recognise the fact that Spain had to deal with a range of migrant-related challenges,” Salonius-Pasternak said. “But the fundamental point of actually increasing defence capabilities still stands.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.