Europe’s efforts to rearm have moved into overdrive. A flurry of European Union initiatives, eye-popping defence budgets, and increasingly urgent political rhetoric suggest a continent sprinting to prepare for escalating Russian aggression.

At the Hague Summit in June, European NATO allies pledged to reach 5% of GDP on defence-related spending by 2035, while the EU unveiled its Defence Readiness Roadmap 2030 in mid-October — moves meant to signal that Europe is finally getting serious.

Yet behind the headlines lies a more uneven reality. Despite unprecedented commitments, Europe remains split between countries rapidly expanding their militaries and those still constrained by years of underinvestment and fiscal fragility.

“There are regional differences, especially between southern Europe and the countries sitting on the border with Russia…” MEP Hannah Neumann, a Greens/EFA member from Germany and a leading voice on European defence policy, told The Parliament. “And there are still too many member states who have their national solutions in mind instead of seeing the bigger picture.”

As some member states power ahead and others drag their feet, the risk is Europe cementing a two-speed defence model, one that could leave the continent dangerously exposed and, ironically, echo the very asymmetries that have long strained the transatlantic alliance.

Europe's two-tiered defence

“We have the front-line states that have made a rapid contribution to defence, and states like Poland and Germany are leading the way on the military mass Europe needs,” Daniel Fiott, head of the defence and statecraft programme at the Brussels School of Governance, told The Parliament. “Other states, far from the front line, will balance the response to Russia with their own geographies and strategic interests. This is perhaps a regrettable situation, but it is reality.”

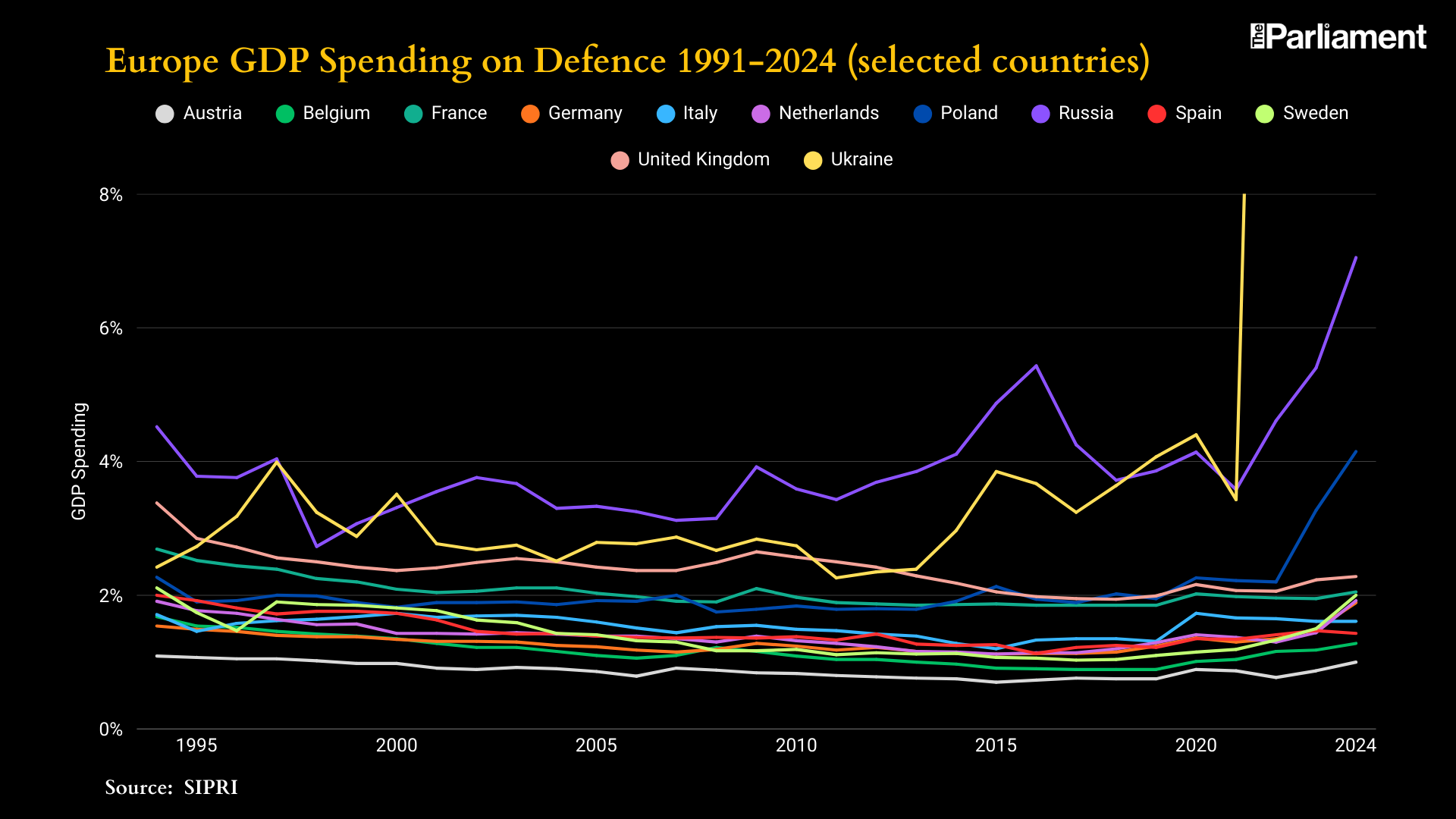

That reality is also reflected in where Europe’s momentum is coming from. Some European countries are pushing European defence forward, powered by a historically strong French military-industrial complex, new purchases of high-tech weapons from the US, such as in Poland, or huge levels of new debt-backed military spending in Germany. In sum, defence spending in NATO Europe and Canada increased by over 15% in both 2024 and 2025, according to NATO.

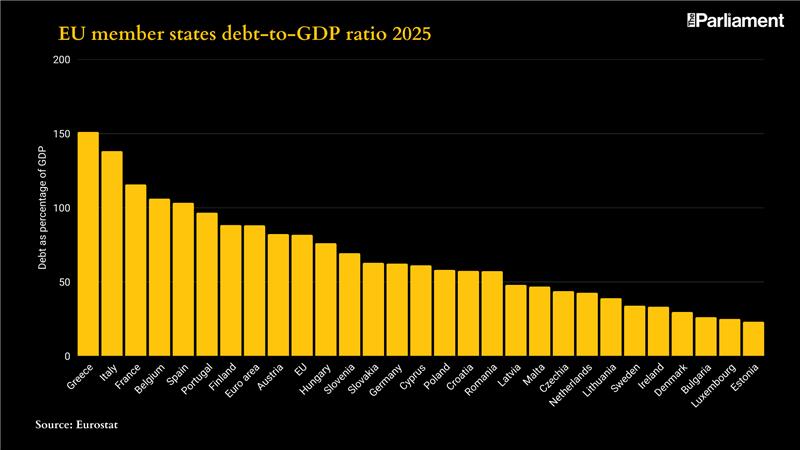

Long-term underinvestment and weak public finances, however, are preventing Europe’s defence laggards — most notably in Spain, Italy and Belgium — from catching up.

After the end of the Cold War, European defence budgets shrank drastically, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). In 2015, EU-wide spending had slipped to just 1.3% of GDP. However, a notable few — including France and Poland — maintained spending at or above the 2% target even during this period.

But others let capabilities atrophy. For Italy, Spain and Belgium, the challenge is particularly acute. All three were some of the lowest spenders throughout the 2010s, and all now need to reinvest heavily to meet NATO standards.

Yet high debt levels and strained public finances make large and rapid increases difficult. Social protection spending — pensions, unemployment, health care — is highest in the most indebted countries, Eurostat data shows, and unions often push back fiercely against welfare cuts in favour of defence.

“You need flexibility in government budgets to adapt to changing times,” Rafael Loss, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations specialising in defence policy, told The Parliament. “Some countries have shown much more political willingness to show their populations it’s time to shift spending.”

Southern states falling behind defence spending

Italy and Spain – Europe’s third and fourth largest economies — illustrate the scale of the challenge and the risk to Europe’s collective defence.

In Spain, Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has refused to pursue the 5% defence spending target promoted by Trump, insisting that Spain will spend “2.1%, no more and no less.” Spain remains the lowest defence spender in NATO at just 1.28% in 2024 — a stance Trump has called “unbelievably disrespectful” while threatening Spain with tariffs. Domestically, however, Sánchez’s resistance has played well with his left-wing base, which prioritises welfare spending. His government even cancelled a deal to buy American-made F-35 fighter jets this summer.

To edge toward 2%, Spain has increasingly relied on mid-year budget modifications rather than the politically sensitive annual budget process, according to Sergio López Caro, an economist at Moody’s Analytics. He notes this approach is a pragmatic way for Sánchez to avoid stiff resistance from coalition partners and the general public.

“Spain’s shortfall in military expenditure does not stem from negativity towards investing in defense per se, but from a desire to constrain the overall pace of expenditure growth,” López Caro told The Parliament. “That’s because the government, and especially the coalition partners, perceive further increases in the military budget as counterproductive, given the already-tight fiscal space and future expenses in social areas.”

Still, these roundabout funding measures mean Spain — one of Europe’s fastest growing economies — is still far from fully committing to the broader defence push.

“European security would look much more robust if Spain made an honest effort to pull its weight in terms of percentage of GDP to defence,” said Loss

Italy’s picture is similar, despite the ideological differences between its government and Spain’s. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has signed on to the 5% NATO target, but Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio — nearly 140% — makes that goal far-fetched. The country hasn’t hit the 2% spending target since 1989, according to SIPRI. Rome is currently under the EU’s excessive deficit procedure until 2026, with its defence minister saying increases will only begin once the country exits the framework. To help close the gap between 2% and 5%, Meloni’s government has even pitched that major infrastructure projects, like a proposed €13.5 billion bridge over the Strait of Messina, could be counted as dual-use military spending.

Furthermore, many Italians simply don’t see Russia as a direct threat, and some worry that higher defence spending could increase, rather than reduce, the likelihood of conflict.

“Spain and Italy are contributing to European security in various ways, by focusing on the southern flank of the EU and NATO by facilitating relatively large and robust defence industries,” said Loss. “It’s not like they are doing nothing. The question is, with the rising geopolitical challenges, as some of the bigger member states, are they doing enough?”

The consequences of this imbalance are significant. Smaller European countries may increase their spending, but their industrial capacity is limited, Fiott said. That makes the buy-in of the largest countries all the more important for Europe’s defence to reach a critical mass.

There are political implications too. If the defence asymmetries within Europe continue to expand, it could put more pressure on the EU’s existing architecture for foreign policy decision making. That could heighten longstanding calls to reform the Common Foreign and Security Policy by having it operate around qualified majority voting — a change that would benefit larger member states.

Belgium's spending lags, Nordics show they way

Belgium is another laggard. Chronically low defence spending, high debt, and recruitment challenges have left its armed forces depleted.

As Wannes Verstraete, an associate fellow at the Egmont Institute and an expert on Belgium defence policy, wrote of Belgium’s 2025 Strategic Vision: “The message to allies and the population is to temper their expectations. Instead of being ready in a couple of years, the transformation of the armed forces will only be completed after 2035.”

Belgium avoided a government collapse with a late-November deal to lock in defence spending at 2% of GDP until 2029, but even getting to 2% required some financial acrobatics — making it unlikely that Belgium will go further.

“Stagnating the budget at 2% may result in Belgium further lagging behind if other allies go faster towards the 3.5% defence spending… which a majority of them probably will do,” Verstraete told The Parliament.

Yet Europe does have examples of rapid, determined military transformation. Loss pointed to Finland, Sweden and Denmark — once low spenders or non-aligned states — which have become some of Europe’s staunchest defence advocates since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Their ability to shift quickly reflects political consensus, fiscal commitment and a shared view of the Russian threat.

These smaller Nordic states also show the value of collective solutions. Fiott and Neumann argue that smaller countries could make the largest difference by pooling more of their resources in collective EU-level defence projects.

“I would prefer if member states finally understood that now is not the time for national solutions…” said Neumann. “If we spent together and used economies of scale to our advantage, we would get defence-ready much more quickly and cost-effectively.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.