It was supposed to be a show of unity — France’s defence minister meeting with German and Spanish counterparts in Berlin this month to salvage a next-generation fighter jet programme central to Europe’s security future. Instead the meeting isn’t happening.

France’s government is in turmoil, having just appointed a new defence minister on Monday, and the €100-billion Future Combat Air System (FCAS) — once touted as the cornerstone of Europe’s military independence — is now on life support.

The stakes could hardly be higher. With Russia growing more bellicose and the US evermore unpredictable, Europe’s leaders have vowed to take greater responsibility for their own defence. But even as Europe successfully ramps up production for traditional weapons such as artillery and tanks, no European country has the money or technical expertise to develop a next-generation fighter jet within decades. Instead, Europe’s relationship with high-tech weapons replicates its relationship with cutting-edge technology across the rest of the economy — too little, too late.

More countries have instead turned to American-made F-35s, even as they voice concerns about America being a fickle friend. “The issue here is the actual technology dependency of European armies on US technologies,” Guntram B. Wolff, a senior fellow at Breugel, told The Parliament. “And the fighter jet is one very prominent example.”

If the FCAS programme collapses, Europe’s ambitions for autonomy may collapse with it — leaving European skies dominated by American fighter jets for decades to come, and Europe’s dream of strategic autonomy little more than rhetoric.

A legacy of military dependence

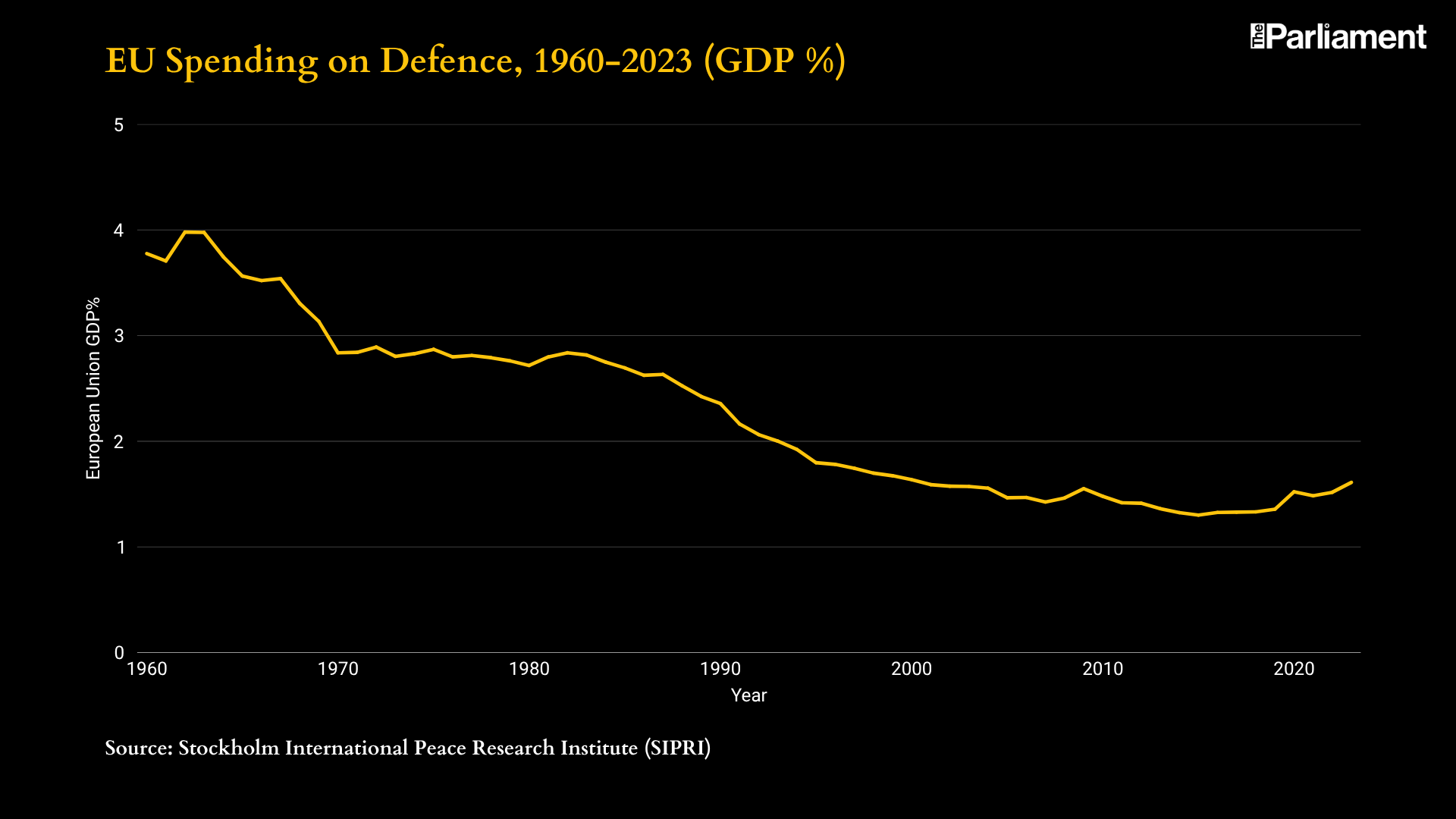

Europe’s technological shortfall has deep roots. After the Cold War, defence spending plummeted from a peak of 4% of GDP in 1962 to a mere 1.3% of GDP by 2015, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The result: a depressed defense industry, and chronically underfunded R&D.

Instead, America has become one of Europe’s biggest weapons trading partners, especially for high-tech weapons like fighter jets and missile systems. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 46% of fighter jets in European fleets are American-made, as are 42% of missile systems. Simpler technologies — artillery, ammunition and armored vehicles — remain largely European-made.

While that has boosted Europe’s military industry, the continent has lagged badly in more complex, long-term programmes. Wolff notes that not enough capital is going into high-tech defence, mirroring Europe’s broader lag in artificial intelligence, software and other cutting-edge sectors, as outlined in the Draghi Report.

The lack of “strategic enablers” such as fighter jets, satellites, command systems, and advanced communications means European armies are still highly dependent on their American partners, and may be for decades to come, Wolff said.

F-35: Dominating European skies

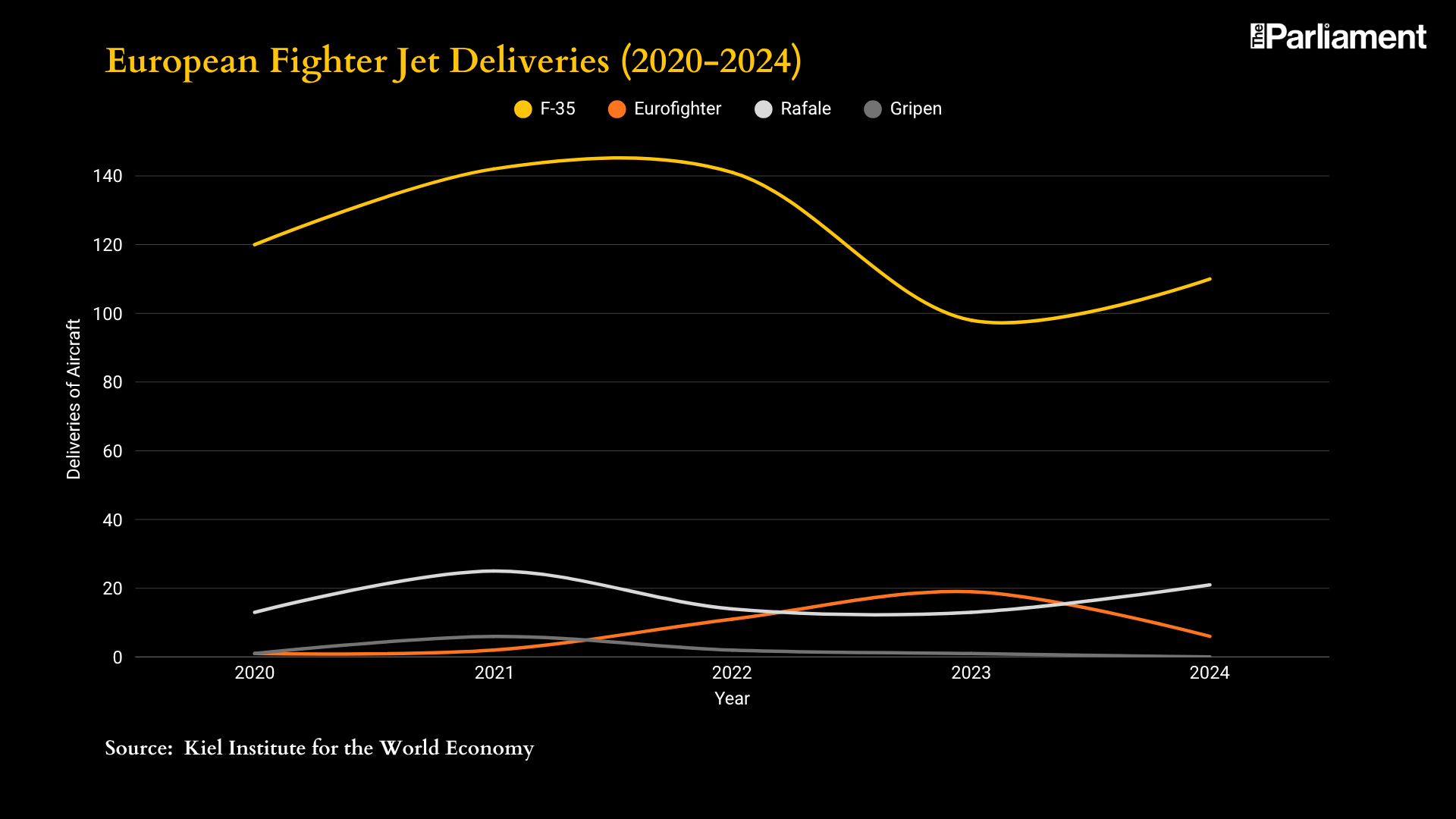

When it comes to high-tech fighter jets, one aircraft dominates Europe’s skies: the American-made F-35. Between 2020 and 2024, European countries received 611 F-35s, according to the Kiel Report, compared to only 135 Eurofighters, Rafales, and Gripens combined — fighter jets made by European firms.

The F-35 is technologically superior to the older European options, and few European countries are willing to compromise.While hundreds of Eurofighters are still in service across Europe, and the aircraft has gotten important upgrades in recent years, it is nonetheless an aging, fourth-generation model from the 1990s. Similarly, the French-made Rafale harks back to the early 2000s and is in need of an upgrade to carry France’s nuclear arsenal.

“For European allies, the F-35 is the most high-tech and capable fighter jet available,” said Wannes Verstraete, an associate fellow at the Egmont Institute specializing in deterrence and arms control. “If you compare it with the capabilities of a Eurofighter or a Rafale, the F-35 is a whole other beast.”

Despite early enthusiasm — when development partners such as the United Kingdom, Italy, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway bought the plane en masse — the F-35 boom has slowed since US President Donald Trump took office. Spain and Portugal have cancelled purchase plans, Switzerland is considering downsizing its order after crushing tariffs and cost overruns, while German lawmakers fear a US “kill-switch” could disable the jets remotely.

In Denmark, the criticism has been ever sharper. “As one of the decision makers behind Denmark’s purchase of F35’s, I regret it,” said Rasmus Jarlov, the chairman of Denmark’s Defense Committee on X. “I can easily imagine a situation where the USA will demand Greenland from Denmark and will threaten to deactivate our weapons and let Russia attack us when we refuse… We must avoid American weapons if at all possible.”

Wolff warns that such dependence extends beyond procurement. “You depend on the supply of the fighter jets and the associated equipment and the approval of the US government,” he said. “And even if you have ordered it and you have it in your hangar, there’s a constant dependency in terms of technology and the software.”

Yet even governments eager to ‘buy European’ face a harsh reality: there are no competitive European options.

FCAS: Europe’s high-tech hope

FCAS was designed to change that — Europe’s answer to the F-35 and a cornerstone of future air power. But it’s still decades away from delivering planes, if it ever does.

“When will significant numbers of FCAS fly combat missions? When will it be operational? In the 2030s, but probably in the 2040s,” said Verstraete. “That’s a gap in European fighters for two decades… In the next decade there is nothing else available but the F-35 for next-generation air power.”

Europe has tried to develop a plane jointly before. In the 1980s, a consortium including the UK, Germany, Spain, and Italy developed the Eurofighter, while France withdrew to develop the Rafale independently following disagreements over design and workshare — a split that now threatens to repeat itself.

Since 2017 France, Germany and later Spain have led FCAS development. But progress has been derailed by bitter disputes between France’s Dassault and Germany and Spain’s Airbus over control of the New Generation Fighter — the programme’s core aircraft. Dassault CEO Éric Trappier has even suggested Dassault could complete the jet alone, undermining the project’s multi-national nature.

Attempts to resolve the dispute have failed. A July meeting between then-French Defence Minister Sébastien Lecornu and his German counterpart Boris Pistorius ended without agreement. Since then, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz has warned that if disagreements persist beyond this year, the €100-billion programme could be scrapped.

“There are increasing reports that there still isn’t an agreement on the basement characteristics of the airplane. Its size, range, and cost,” said Emil Archambault, a fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations. “If the project is eight years in and we still can’t agree on how big the aircraft will be, then it’s a wonder if there is any possibility of it moving forward at all.”

The repeated collapse of the French government also adds fresh uncertainty. Recently re-appointed prime minister Sebastien Lecornu — the former French defense minister and one of few figures with the clout to push Dassault into compromise — is busy cobbling together a new government that many fear will be as short-lived as the last.

If FCAS fails, Germany could consider adding Sweden, which has experience producing fighter aircraft, to the FCAS programme, or alternatively pivot to Global Air Combat Programme (GCAP) — another fighter jet programme developed by the UK, Japan, and Italy. Archambault said it would be highly unlikely for Germany to buy even more American planes.

“It would be politically and strategically bad for Germany and the EU, if FCAS failed and they felt they had to buy more F-35s or the upcoming F-47,” said Archambault, referring to the next generation of American fighter jets that is already in development and slated for first flight in 2028. “That would be extremely damaging for EU strategic autonomy."

Europe at strategic crossroads

Europe wants to boost defense spending, rebuild high-tech industrial capacity, and achieve strategic autonomy. Yet it's hobbled by decades of underinvestment, technological lag, and political infighting. As Archambault noted, it’s unlikely that any European country alone could develop a sixth-generation fighter aircraft in the coming decades. The technical challenges are too great, and so are the costs.

If FCAS collapses, in other words, the consequences will reverberate for decades. Europe could remain reliant on American fighter jets well into the 2040s — precisely the future its leaders have long sought to avoid.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.