If we turn our gaze back to 19th-century Europe, we see in the very heart of the continent something called the shatter zone of empires. There, the spheres of interest of all the great European powers cut into one another, turning this area into a geography dripping with blood. All the shattered nationalities were pitted against each other by active agents and imperial policies. At the same time, and by the same token, all grievances – and there were a lot of them – were used to prevent the small, subdued nationalities from forming a functional identity and finding a common way to independence and peace.

In the aftermath of the First World War some of these states were able to escape. That was the case for Finland, Poland and, for a while, the Baltic States. Yet some other states were constructed or reconstructed under the controlling eyes of the victorious, and thus surviving, empires. Therefore, most of them were unstable from the very beginning and easily morphed into petty dictatorships later down the line.

Probably the most dramatic but least observed change happened inside the borders of the former Russian Empire. The Russian revolution fed illusions to these small nations about “liberté, égalité, fraternité”, which then, after the forced collectivisation and the great terror, turned into “fratricide, dictature, famine”.

With the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, Joseph Stalin decided, under the pretext of security, to revert to the borders of the Russian Empire. That was the starting point of the Soviet Russian re-occupation of the Baltic States and the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union. Soon after, the Second World War made a hell out of the remnants of this shatter zone.

Finland escaped the fate of the other European states inside this imperial or comradely Russian sphere of influence, but the price to be paid included severe restrictions on the country’s ability to choose its own trajectory

When you compare the outcomes of the First and the Second World Wars, there is one structural property standing out, especially if you also consider the political changes after 1948: the Russian Empire was reconstructed. The nice, but in a context of realpolitik probably naive, Wilsonian intentions after the First World War had been revoked.

Finland escaped the fate of the other European states inside this imperial or comradely Russian sphere of influence, but the price to be paid included severe restrictions on the country’s ability to choose its own trajectory. The peace agreement from Paris restricted both the army and the possibility of joining any organisation on the western side of the iron curtain.

The rest was taken care of by the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance of 1948. The short-lived thaw in east-west relations around 1956 opened up some space. In small and carefully choreographed moves Finland was then able to join the Nordic Council, the United Nations and, eventually, the European Free Trade Association.

The Finnish tactics of using any relaxation of tensions between the superpowers fed the idea of the Conference of Security and Cooperation held in Helsinki 1975. But the basic conviction up to 1989 was that the Soviet Union was there to stay and very little, if anything, could be done to change or loosen that foundational bolt in the European security system.

Then everything changed with the collapse of the imagined Soviet giant. Finland recalibrated its security policy by joining the European Union and was convinced that the security the EU could offer was enough. The thought of also applying for membership in Nato seemed for most Finns to be far outside both the country’s security needs and the realms of political imagination.

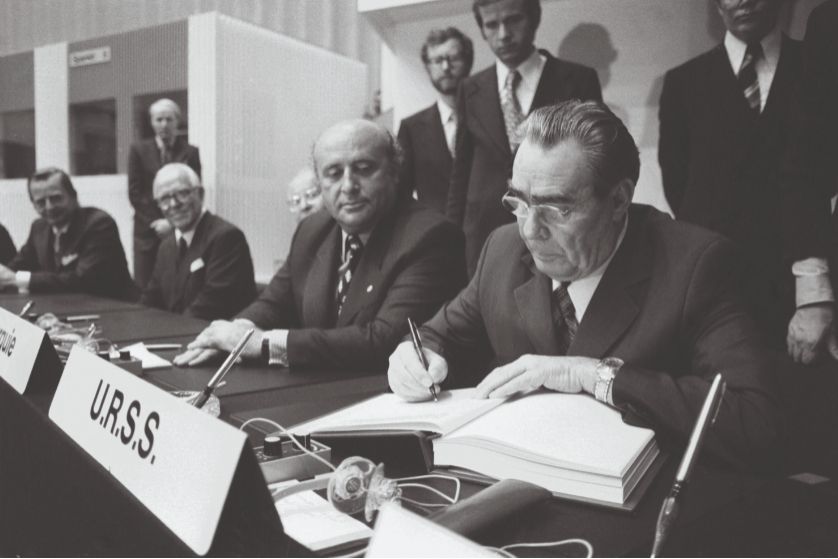

Security and Cooperation conference held in Finland, 1975. Photo: Alamy

But some parts of the European hard structures were never really analysed. The First and the Second World Wars had basically shattered the old empires – with one interesting exception. Very few pundits of international relations understood the implications. Normal European states had created national identities. But Russia never created a national identity in the true sense of the word. Instead, Russia created a great power identity which was deeply rooted in the siloviki elite. Due to a very diminished civil society, no challenging democratic identities were able to compete in the strictly closed and controlled Putinist Russia.

That made Russia very dangerous, especially as the economic base was doomed to be undermined by the shift to a carbon-neutral world economy. All this became apparent for the world on one single day: 24 February 2022.

The traditional saying in any Finnish debate on security policy had been that the population would follow if the Finnish political leadership pointed towards Nato membership. Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine changed something substantial: the people turned to Nato and the politicians had to rearrange their faces and their speeches.

Suppressed memories from the Winter War of 1939 came alive, and Finland decided to ask for membership. I’m guessing that the political machinery will do that in June, at the latest.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.