For decades, the European Union couldn’t have imagined turning off the tap on its steady stream of cheap, abundant natural gas from Russia. Now, Brussels says it’s ready to make a clean break. But as the bloc struggles to speak with one voice, cutting the last ties to Russian energy might remain just that — a pipe dream.

The European Commission on Tuesday unveiled a long-anticipated roadmap outlining the steps required to eliminate its remaining gas and nuclear imports from Russia. The plan — twice delayed due to geopolitical turbulence — finalises a strategy hastily drafted in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

“By the end of 2027 we will be completely free from Russian gas,” Dan Jørgensen, the EU’s commissioner for energy, said as he presented the strategy. “Even if there was a peace tomorrow [between Russia and Ukraine], still it would not be sensible of us to become dependent on Russian fuel again,” he told reporters.

Russian President Vladimir Putin, Jørgensen added, “has shown that he doesn’t mind weaponising gas.”

But the Commission’s bold plans could prove to be more aspirational than transformational, given Brussels’ limited capacity to compel EU companies to comply.

“It’s more of a signal — a symbolic measure rather than one that will have tangible effects,” said Philipp Lausberg, a senior policy analyst at the European Policy Centre (EPC). “At the end of the day,” he argued, “it will be companies that make their own calculations.”

According to Lausberg, the Commission’s plan is meant to transmit a strong political message to Moscow — affirming the EU’s continued support for Ukraine — but is unlikely to result in the complete cessation of Russian gas imports.

Still, the Commission is set to propose legislation next month that would effectively require EU energy companies to halt purchases of Russian gas on the spot market and terminate existing spot contracts — together accounting for roughly one-third of current imports — by the end of this year.

The bill will also target gas arriving via the TurkStream pipeline and Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) tied up in long-term agreements, with the latter expected to be phased out by 2027. Additionally, the legislation will address Russian nuclear fuels, which continue to be imported by five European countries, despite failing to set a specific date for a phaseout.

Under the bloc’s initial RePowerEU programme, EU countries already committed to phasing out Russian oil and gas entirely by 2027 — but the pledge was non-binding.

The move is intended to mark another key step in the EU’s efforts to free itself from Russian energy, following its sanctions on Russian crude oil and coal in successive packages released in 2022. EU imports of Russian crude — which comprised roughly 80% of the country's fossil fuel revenues, compared to just 20% from natural gas — have plummeted to just 3% from 27% since 2022, according to the Commission.

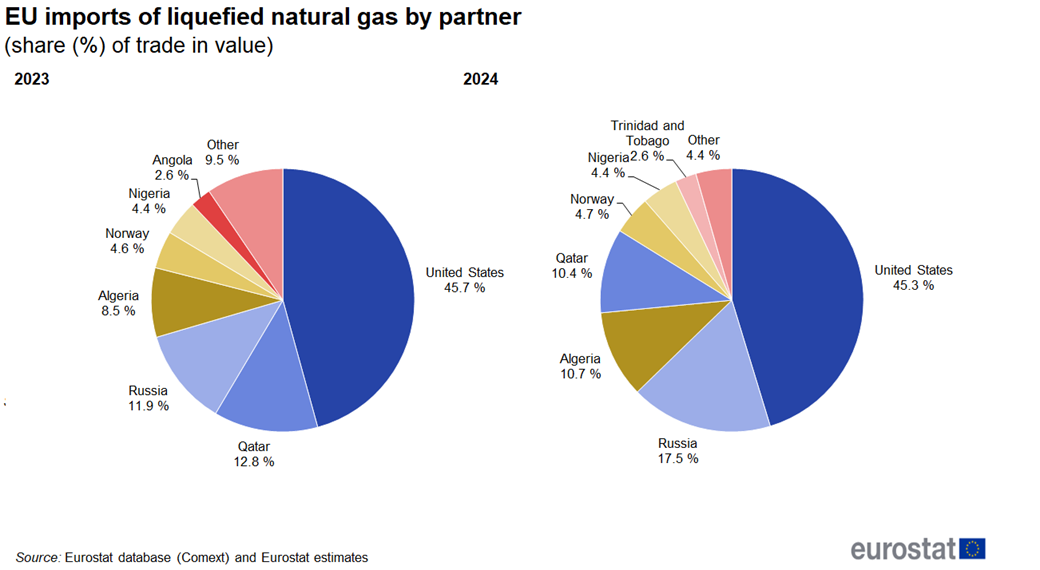

While the EU has significantly reduced its reliance on Russian gas from both pipelines and LNG — to 19% from 45% between 2021 and 2024 — last year’s imports of Russian LNG by volume grew 12% year over year, according to the Commission. In monetary terms, the EU spent 5.5% more on Russian LNG in 2024, according to Eurostat, making Russia the bloc’s second biggest supplier after the United States and ahead of Algeria and Qatar.

Tuesday’s announcement comes as Brussels is looking to leverage its increased LNG purchases from the US as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the US administration to try to stave off a 20% tariff rate on EU goods that could come into effect by summer.

A fragmented Europe

Despite Von der Leyen’s efforts to project political unity, the question of whether to ban Russian LNG or keep it flowing has become a source of deep division among EU member states. Earlier this year, ten EU countries — Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Ireland — urged the EU executive to crack down on ongoing LNG imports from Russia, claiming that a failure to do so amounted to pouring billions of euros into Russia’s war chest.

Meanwhile, Tuesday’s proposal faced stiff opposition from Hungary and Slovakia — two countries whose leaders are closely aligned with Putin — both of which warned that banning Russian LNG would prove too economically painful.

Other politicians across the bloc still refuse to rule out a return to Russian gas via Nord Stream 2, a natural gas pipeline linking Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea. The controversial project, which never became operational, came to a sudden halt in February 2022, just days after Putin invaded Ukraine. Months later, in September 2022, a string of undersea explosions significantly damaged Nord Stream 1, shutting down the pipeline that had been operational since 2011.

Some politicians in Germany’s centre-right Christian Democratic Union, which officially opposes imports of Russian energy, have openly toyed with resuming the Nord Stream gas flows.

“When peace returns and the weapons between Russia and Ukraine fall silent, relations will normalize, sanctions will be lifted, and of course, gas can start flowing again — perhaps this time through a pipeline under U.S. control,” Christian Thomas Bareiß, a negotiator for infrastructure policy in the new German coalition government, wrote in a recent LinkedIn post.

Italy’s energy minister, Gilberto Pichetto Fratin, said late last year that Rome would not be against resuming gas imports from Russia as part of a broader attempt to curb energy costs.

The lack of consensus is why Brussels ultimately dropped a proposal to sanction Russian LNG, given such a move would have required near impossible unanimity among member states. The new strategy has the advantage of requiring only qualified majority voting among member states in the European Council, essential to sidelining opposition from Hungary and Slovakia.

Opting for sanctions, however, would have enabled EU companies to more easily invoke force majeure and terminate existing contracts without incurring hefty penalties. Most long-term contracts include so-called take-or-pay clauses, which require companies to pay most of the agreed price even if they cancel a deal.

While experts have raised significant doubts about companies being able to avoid legal repercussions, the Commission on Tuesday insisted that its proposal would provide enough legal heft for the bloc’s oil-and-gas firms to call for force majeure without facing significant liabilities.

Anatomy of a phaseout

The EU has already demonstrated it can do without Russian gas. That’s largely thanks to diversification efforts spearheaded immediately after the start of the war in 2022. By 2024, Europe’s largest gas suppliers in absolute terms were Norway, Russia and the US, according to the International Energy Agency.

Still, going cold turkey on Russian fossil fuels could put already ailing European manufacturers in a difficult spot, with fewer options on where to source energy to power their operations.

“The LNG market is still quite tight this year,” said Alex Froley, an LNG analyst at energy consultancy ICIS. Though, he noted that prices have eased in recent weeks amid expectations of a weaker global economy due to US President Donald Trump’s trade wars. Energy prices come under pressure when GDP contracts, reflecting a decline in industrial activity.

Sky-high electricity costs for industries and households remain a politically sensitive issue in the EU, as the bloc grapples with energy prices up to three times higher than those of its global peers in the wake of the Ukraine war. The Commission is currently working on legislation to rein in prices by accelerating electrification efforts.

Still, Froley noted that global LNG supply is expected to grow in the coming years, which would make it easier for the EU to secure alternative suppliers at more reasonable costs.

“There will be a lot more LNG available later this decade,” he said, noting that new North American projects are expected to come online by 2027, while Qatar is planning to double its exports by the end of the decade.

Ditching Russian gas would likely draw European firms further towards US supplies, potentially swapping one dependency for another, experts say.

Ultimately, the question will be “at what price it makes sense to disentangle [from Russia] and create new dependencies [with the US],” one EU diplomat, speaking on the condition of anonymity, told The Parliament.

“The last mile is always the most difficult one — the most difficult and the most expensive,” he added.

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.