Geneva’s Museum of Art and History has recently unveiled an exhibit it has been preparing for the past five years: a posthumous show of work by Turkish modern artist Burhan Doğançay.

The exhibit, entitled The Walls of Burhan Doğançay, features more than 50 pieces donated by the artist’s widow, Angela Doğançay, after his death in 2013. Her gift fulfils his wish to share his work with museums that will preserve his art for future generations, beyond the private interests of the marketplace.

Across a single wall in the classically renowned museum, all his artworks are framed – bar one. The unframed piece, Gerber's Baby – Ben Zion St., is a collage made from materials including sand, coffee, newspaper, metal and smoke, gathered while Doğançay photographed Israel’s walls for his compositions.

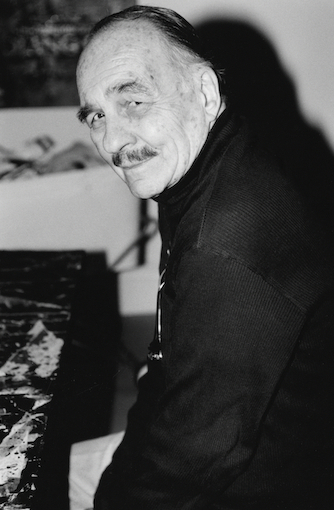

Doğançay, 1996. Photo by C. Dosembet

Doğançay, 1996. Photo by C. Dosembet

Between the grouped artworks and the unframed piece, a book of preliminary sketches is displayed, demonstrating Doğançay’s understanding of the dialogue between painting and photography.

While earning his doctorate in economics at the University of Paris, Doğançay studied art at the L’Académie de la Grande Chaumière in the early 1950s. Despite his successes, fellow artists in Turkey and the United States would consider him an outsider.

Doğançay's career obsession with walls began soon after his arrival in New York in 1962 when, on an uptown walk, the modernist aesthetic that would define his life’s work appeared to him as he appreciated the collective public art of accumulated ephemera posted on the city walls.

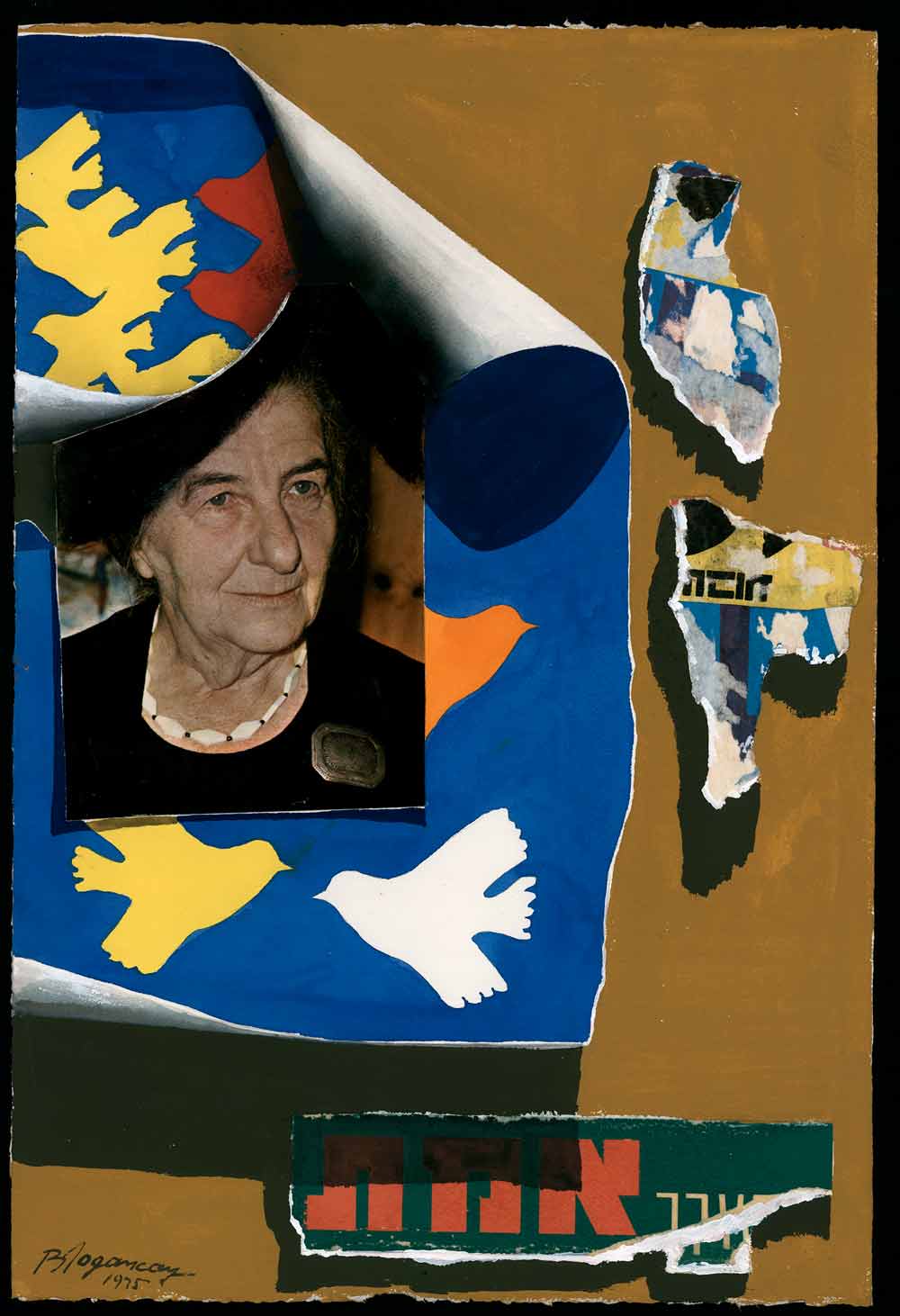

© Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

© Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

His widow recalls an early initiative that would prove to be the catalyst for his longest-running project, which would later develop into his Walls of the World series: invited by an Israeli colleague from the diplomatic service, he boarded a plane to Tel Aviv in 1975. He returned home with suitcases full of grimy posters, stripped from urban walls in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.

Doğançay’s intention was to produce modern artworks using elements found during his travels, combined with photographs recording his observations. He adapted the methods of décollage, in which images emerge out of processes of fragmentation.

In total, Angela accompanied her husband to 16 countries, travelling to South America, parts of Africa and across Europe. She remembers that, when in Switzerland, Doğançay became aware of strict local laws concerning public property. He dutifully avoided contravening the regulations himself; instead, asking her to tear posters from the walls. Her participation is just one example of her lifelong commitment to the production and dissemination of his artwork.

“I was going from gallery to gallery with his portfolio, trying to organise exhibitions,” she tells The Parliament. “One day, when he was travelling, I [emailed the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to] offer a portfolio of his lithographs from the Tamarind – a prestigious workshop in Los Angeles. I asked the Met if they would be interested, and they immediately came back to me and said, yes.”

That was in 2004. The current exhibition in Geneva was met with equal enthusiasm by those working at the city’s Museum of Art and History – albeit with an appreciation for Doğançay’s process rather than the finished result.

“Contemporary art is not my forte,” admits Bénédicte de Donker, a medievalist by training, and one of the curators of Doğançay’s exhibit. “In terms of craftsmanship, I’m not very impressed. It’s good but nothing out of the ordinary. I’m more interested in his process, the fact that he photographed walls in 114 countries, and what he did with his archive, how he transformed it into his work.”

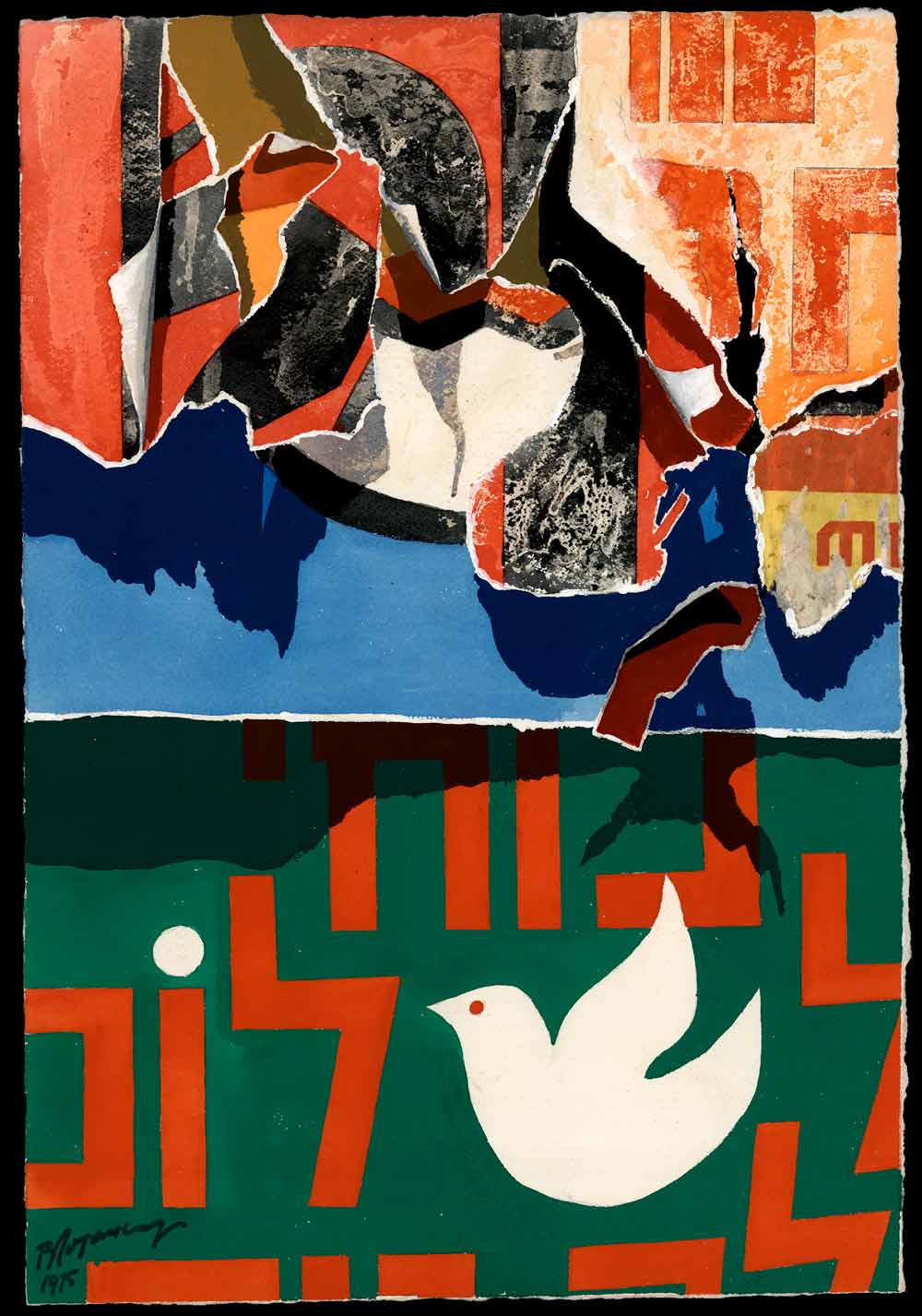

.jpg) © Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

© Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

When it comes to the works in the exhibit, de Donker was struck by the range of colour and the universality of wall signage that Doğançay accumulated, creating a global visual vocabulary. In that sense, the exhibition sets out the notion that, rather than dividing, walls can signify unity.

Doğançay was inspired by the wave of pop art sweeping New York in the second half of the 20th century through artists such as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg.

“You can see some similarities” between his work and Rauschenberg’s, says Yahşi Baraz, a Turkish art dealer who met Doğançay in 1975, and exhibited his solo show that year, following his return from Israel. “His name is not in the new realism books. They don’t accept his style. I’m surprised,” Baraz adds. “He’s a mix of pop art and graffiti art. Time will show.”

He returned home with suitcases full of grimy posters, stripped from walls in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem

Doğançay had taken art courses while completing his economics PhD at the University of Paris. His father, Adil Doğançay, was also a painter, military-trained from Istanbul, who passed on his passion for oils and travel.

As post-war Paris reeled with poverty and nostalgia, the global art world shifted from Europe to America. By the 1960s it was defined by names such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell – just in time for Doğançay to show paintings beside Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Willem de Kooning, representing Turkey at the World Show exhibition at Washington Square Galleries in New York. In 1963, he resigned from his job as a bureaucrat and went into art full time.

“In 1945 [he made his] first attempts to be famous as an artist in America,” Baraz explains. “When Burhan came to New York in 1962, everyone was settled down,” he adds, remembering his many trips to New York with Doğançay in the 1970s. “American art critics knew who the American artists were. They didn’t accept Burhan’s name as an American artist."

© Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

© Estate of Burhan Doğançay © Musée d'art et d'histoire de Genève

Rauschenberg was a big influence in Tel Aviv as well, says Leah Abir, a Tel Aviv-based curator. “Walls were a big reference, especially for the Tel Aviv group. There’s lots of reconsiderations of the 70s, mainly post-war. Doğançay looks very ‘naïve',” she says, using a term from the art world that means ‘untrained’. “You can find ads, text, print in the Israeli art,” she adds, “but it looks completely different.”

In 1975, Doğançay climbed the steps to the newly founded Gallery Baraz, still located at the same address in Istanbul. Taken by his affinity for modernism and his friendly character, Baraz befriended Doğançay and organised his first show, pivotal for both their careers. Doğançay sold well and later went on to become the first Turkish artist in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

There was backlash within Turkey’s relatively rarefied art world. Local artists saw him as an outsider from New York, a lawyer and bureaucrat without formal art school training. Collectors, it seems, had other ideas. In 2009, his piece, Symphony in Blue sold for $1.7m (€1.6m).

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.