When the European Union signed its trade deal with Washington this summer, Brussels framed it as a diplomatic win: tariffs capped at 15%, a trade war averted, transatlantic ties repaired — and a chance to accelerate the phasing out of Russian energy, which was already underway.

But the actual price tag? A whopping $1.35-trillion commitment through 2028: $750 billion in US energy purchases and $600 billion in fresh European investment across the Atlantic.

European Commission officials insist the numbers are achievable, casting the deal as both pragmatic and strategic. But critics see a lopsided bargain, a surrender that locks Europe into costly dependencies, undermines the bloc's climate goals and makes promises Brussels cannot enforce on private companies.

Indeed, even approaching the pledged sums would demand a radical reshaping of Europe’s energy mix and investment flows at a moment when its own industries are under pressure to reindustrialise. And the deal comes with teeth: miss the targets, Trump warns, and American tariffs on EU goods could jump to 35%. In other words, what the Commission hails as transatlantic unity and sound economics is, by the math, a promise that looks nearly impossible to keep.

Can Europe really buy that much US energy?

Under the deal, Europe has pledged to lift US energy purchases from $80.5 billion in 2024 to $250 billion annually through 2028. That leap is “just massive,” said Arturo Regalado, an energy analyst at Kpler, implying either a six-fold increase in liquefied natural gas or a wholesale diversion of US crude oil from Asia to Europe.

Negotiators, though, argue the goal is realistic, given Europe’s push to eliminate Russian gas — reinforced last week as the Commission moved to ban Russian LNG after fresh threats from Trump.

However, even replacing all Russian imports with American energy would barely dent the total figure agreed. In 2024, the EU spent only €7 billion on Russian LNG and another €10 billion on pipeline gas, plus a trickle of crude — roughly $25 billion combined. That still leaves a gaping hole in the $250-billion annual promise.

Crude oil from the US is also a poor fit for European refineries, which were built for Russian grades and are shrinking in number. The EU imported around $40 billion in American crude in 2024; analysts at Kpler think the bloc could stretch that by perhaps $6-7 billion more. And that constraint is mirrored on the American side: the US exported only $166 billion in oil and gas worldwide in 2024, much of it locked up in long-term contracts, according to Regalado. Redirecting that flow wholesale to Europe isn’t a realistic option.

Even if it were, Europe’s demand is heading the other way. Warmer winters, the spread of heat pumps, and renewables in Europe are all expected to cut fossil-fuel use. “There is not enough demand to absorb all of that energy that the US wants to sell us,” said Ana Maria Jaller-Makarewicz, lead European energy analyst for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “The US is offering us a huge menu, but how much can we buy?”

The only way to even approach that target would be for the US to significantly ramp up production while Europe overbuys beyond market needs, or alternatively for nuclear energy exports to carry a large share. US Energy Secretary Chris Wright said last week that new nuclear projects in Europe could make up to one-third of the total $750 billion import promise. But even then, oil and gas would still need to cover the bulk.

From Moscow to Washington: trading energy dependency

Even if numbers could be met, critics warn the EU is just trading one dependency for another. As 2022 showed, Europe’s reliance on Russian gas left it painfully exposed when Moscow shut off pipelines, triggering soaring prices and rationing across the continent. In the first half of 2025, the US already supplied 55% of Europe's LNG, up sharply from 2021. To hit the new target, that dominance would only deepen. The EU would need to buy 70% of its imports of gas, oil, and coal from the US to reach $250 billion in annual spending.

A group of MEPs led by Christophe Grudler (FR, Renew) have sent a letter urging the Commission to drop the purchase commitments, warning the deal undercuts climate goals and opens the bloc to “political blackmail” if targets fall short. "The EU-US agreement on energy commitments runs counter to all our objectives, whether in terms of climate action, economic sustainability, or industrial sovereignty," Grudler told The Parliament. "Committing to $250 billion per year for US energy products is not only environmentally irresponsible but also economically incoherent."

Infrastructure investments also cut both ways. Since 2022, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy have built new LNG import infrastructure, but with capacity far outpacing demand, Europe may be left paying for costly infrastructure simply to justify imports of American gas. Even so, neither the Commission nor the White House can tell private companies where to sell their gas or oil, according to Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a global research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy. That means regardless of the deal’s language, market dynamics and price differentials will play the key role.

The $600 billion beyond Brussels’ control

The other half of the bargain is $600 billion in new European investments in the US across all sectors of the economy. Trump has boasted this will be a “gift” he can spend as he wishes. In reality, it’s nothing like Japan’s government-managed investment fund that was central to the Japan-US trade deal. Here, the figure is based entirely on private capital flows — like European companies building auto plants or pharmaceutical hubs in the US — which Brussels cannot command. The Commission was later forced to clarify that the $600 billion sum came from EU companies which had “expressed interest in investing” at that scale.

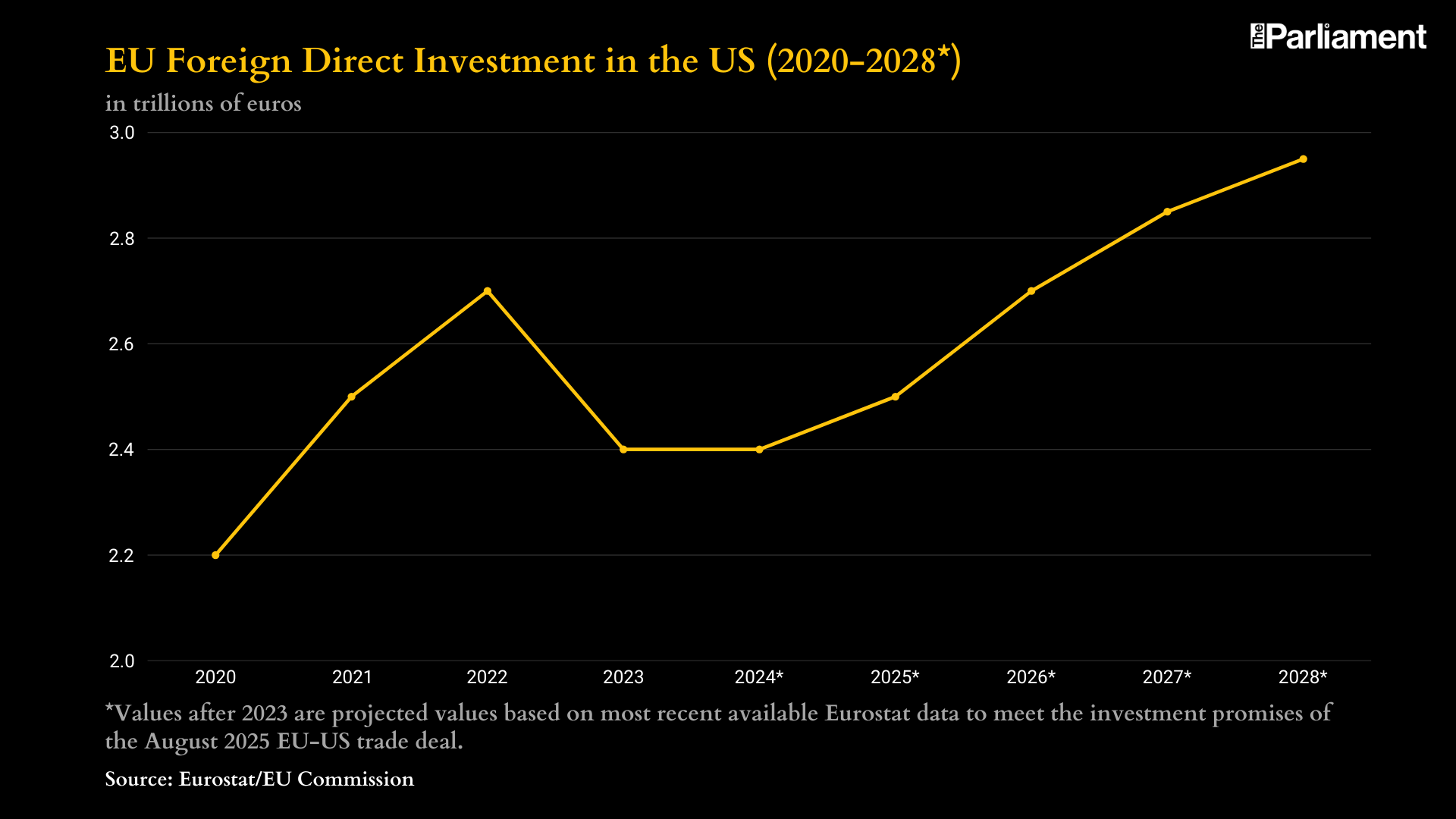

But history suggests the gap is wide. As of 2023, the most recent year for which data is available, the EU’s foreign direct investments in the US totalled €2.4 trillion ($2.8 trillion), according to Eurostat. Over the three years prior to 2023, that figure increased by an average of around €65 billion ($77 billion) per year. Hitting the $600-billion mark would mean tripling that pace at a moment when some of Europe's own industries are struggling at home.

To Arthur Leichthammer, a policy fellow for geoeconomics at the Jacques Delors Centre in Berlin, the real danger is political: Trump now has a benchmark he can wield if Europe falls short, justifying threats of new trade measures. He also stressed that in today’s trade wars, security and economics are intertwined. With American military backing still vital for Ukraine, Brussels had little room to resist, leaving it to swallow provisions built on pie-in-the-sky energy and investment numbers.

As Leichthammer puts it, trade outcomes in the Trump era ultimately reflect “the risk appetite and leverage of US trading partners — how much pressure they can exert, and how far they’re willing to push back.”

Sign up to The Parliament's weekly newsletter

Every Friday our editorial team goes behind the headlines to offer insight and analysis on the key stories driving the EU agenda. Subscribe for free here.